Having returned to study in 2023, over the next few weeks I will be sharing my recent assignment in a 3 part series. The assignment is a reflective piece of my thoughts about the persisting view of the biomedical body in pain and physiotherapy practice. In this piece of work I offer 3 perspectives that demonstrate this view resulting in a professional blindness to biomedicine’s infiltration within physiotherapy. Without a deeper analysis of the reasons for this enduring view I argue the futility of using alternative models or frameworks in an attempt to paradigmatically shift healthcare practice. I hope you enjoy reading as much as I did writing.

Introduction

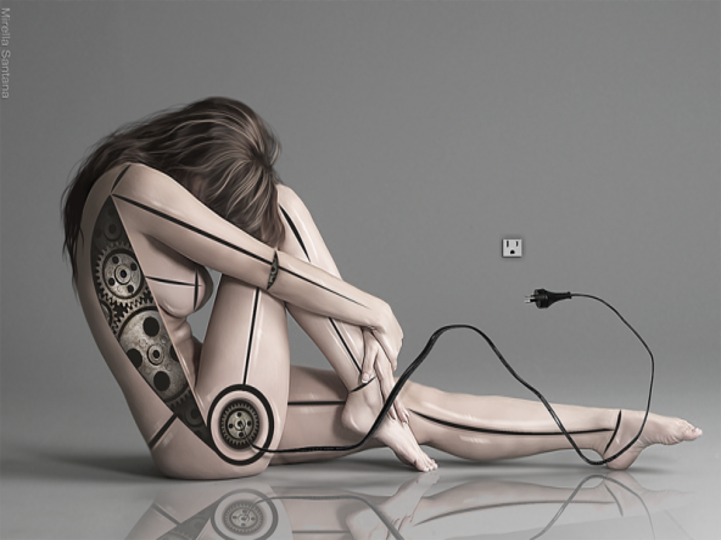

Biomedicine’s declaration that pain is a deviance to be removed from the body is a prevailing view that can be traced back to Cartesian mind/body dualism, predominantly Locke’s empiricism and the theory of logical positivism. The combination of these philosophical positions has arguably set the foundations for biomedicine and evidence-based practice (EBP) (Denny, 2018; Maric & Nicholls, 2019). Biomedically, the body is characterised as a machine, reduced into respective parts (biological reductionism), with a particular focus on ‘abnormality’ of the part. Privileging the abnormal or ‘pathological,’ biomedicine’s (and by extension physiotherapy’s) proclivity towards biological determinism suggests that illness is a deviance of normal tissue, and where ‘body-as-machine’ describes a mechanistic view of the body, the ‘sick’ or disabled body represents a faulty one (Fox, 2012). In biomedicine pain is a physical sensation, which infers an objective biological view of pain by reducing it to a complicated transmission of neural signals (referred to as nociception) that convey a malfunction in the physical workings of the body (Bendelow, 2013). Ostensibly, biomedicine proposes disability can be cured, and with it, pain eliminated through medication or medical and surgical procedures (Denny, 2018; Fox, 2012).

Challenging the predominant biomedical view of the body, George Engel, in his classic 1977 article ‘The Need for a New Medical Model: A Challenge for Biomedicine,’ wrote, “I contend that all medicine is in crisis…” (Engel, 1977, p.377). Engel was referring to the divide that had opened between psychiatry and medicine and was opposed to the stronghold biomedicine had through privileging biological determinism and reductionism over other factors that affected bodies (Engel, 1977). This criticism of biomedicine would set the platform for Engel to announce his alternative approach to medical care through his biopsychosocial model (BPSM). Ironically, where Engel was attempting to align psychiatry and medicine, psychiatry would later go on to criticise the BPSM (Ghaemi, 2009; McLaren, 2021).

Forty years on since Gordon Waddell released his seminal article on the BPSM in the management of back pain (Waddell, 1987) research has demonstrated the impact psychological and social factors have on patient outcomes (Edwards et al., 2016; Pincus et al., 2002) and on persistent pain and disability (Ferreira et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2015). Subsequently, the BPSM has been accepted in academic and clinical circles as the preferred model of choice. Despite the efforts of eminent figures within medicine over the last 40 years to release biomedicine’s grip and attempt to resituate pain beyond bodily tissues, biomedicine remains a prevalent force in the domain of pain and physiotherapy. The question here is, why does biomedicine’s stronghold over pain and physiotherapy endure?

Main argument

Arguably, biomedicine ignores the wider socio-cultural and phenomenological or ‘lived experience’ aspects of pain (Denny, 2018) and where the BPSM attempts to paradigmatically fill this gap, it has also been the target of multiple criticisms. For example, that the BPSM lacks philosophical coherence (Benning, 2015), it is anti-humanistic (Ghaemi, 2009), it perpetuates a divide between the biological and psychosocial (Hancock et al., 2011; Low, 2017; Mescouto, Olson, Hodges, & Setchell, 2022; Setchell, Costa, et al., 2017), it fundamentally ignores and misrepresents the social determinants (Mescouto, Olson, Hodges, & Setchell, 2022; Smart, 2023), the general systems theory upon which the BPSM is informed relies on reductionist theories (Tramonti et al., 2019), it lacks a clear theoretical foundation (Bolton & Gillett, 2019), and it is not ontologically grounded (Nicholls, 2022), thus creating an issue in fidelity (Simpson et al., 2021). These issues result in physiotherapists implicitly favouring the biomedical due to feeling inadequately trained (Mescouto, Olson, Hodges, Costa, et al., 2022), and overwhelmed by the complexity of navigating a holistic approach to care (Barradell et al., 2018). It is arguable that perhaps the issue is not the BPSM itself, but the way physiotherapy employs it.

If the BPSM fails to resolve many of the issues faced by physiotherapists in resituating pain beyond the biomedical body, what then is the answer? Recent research has argued that it may be an issue of fidelity to the biomedical model that result in physiotherapists having difficulty using the BPSM (Holopainen et al., 2020).

To explore the issue of fidelity to the biomedical model, the model may be critiqued using an ecological view of curiosity (Grossman et al., 2020). Grossman et al. (2020) conceptualise curiosity as ‘multiple, praxiological, and political’ and state that ‘it has the capacity to upend what we know, how we learn, how we relate, and what we can change’ (p. xiii). Historically, curiosity was regarded as disobedient, disrupting accepted and unquestioned norms, and for those who embodied it were regarded as meddlesome (Zurn, 2021). More recently, curiosity can be described by Shankar as a practice rather than an acquisition of knowledge. He writes,

“Curiosity is not a static trait that one has or does not have but is rather a constantly shifting relation between the knowledge one acquires and how one feels about the knowledge one acquires” (Shankar, 2020, p.109)

Shankar’s description echoes that of Foucault, who stated,

“Curiosity is…a certain determination to throw off familiar ways of thought and to look at the same things in a different way” (Foucault et al., 1997, p.325).

To embrace an ecological view of curiosity I chose to examine other areas of physiotherapy practice, which are commonly (implicitly) overlooked. Using the work of Michel Foucault, I intend to demonstrate a discursive interdependence between science and social practice by discussing three perspectives: 1) The imprisonment of bodies: Institutional and clinical behaviours that fix pain in the biomedical body; 2) Where biomedicine influences physiotherapy research and subsequently clinical practice; and 3) How biomedicine is expressed through the physiotherapy clinic.

We will explore these perspectives in Part 2.

Thanks for having a read

TNP

Leave a Reply